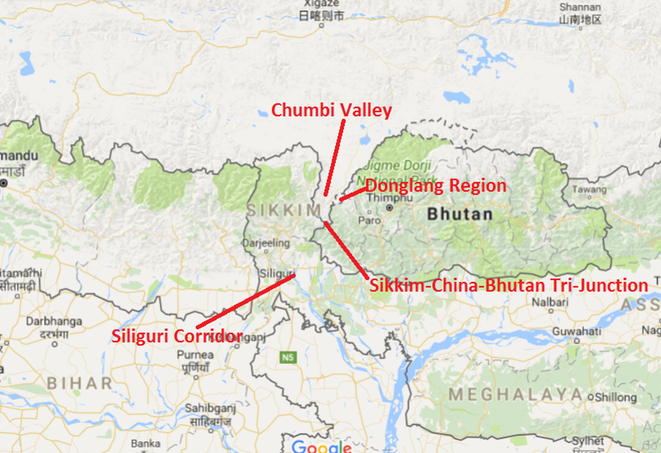

On August 28, India’s ministry of external affairs (MEA) and China’s ministry of foreign affairs announced the end of the stand-off between the troops of the two countries at Doka La in Doklam (Donglam for Chinese) area’s Dolam plateau, which is at the India-Tibet-Bhutan trijunction near the Indian state of Sikkim. The whole area falls under the Chumbi Valley on the south side of the Himalayan drainage divide, which points like a dagger towards India on the map.

The two coordinated announcements brought the curtains down to the 72-day stand-off between troops of the two Asian giants at a desolate location in the eastern Himalayas, which grabbed the world’s attention with concern. Also, many Asian nations with territorial disputes with China, especially in the South China Sea region, waited to see how it ended.

The beginning of the stand-off

In mid-June this year, a Chinese construction party accompanied by Chinese border guards and some People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldiers started to construct a road through the plateau, which is a disputed territory between Bhutan and China, right up to the Indian post at Dokala (Doka La). The road would have given the PLA the ability to move in logistics and heavy military hardware like tanks and heavy artillery in close proximity to the Indian positions on the border in the section, which would have significantly diminished the tactical advantage the Indian Army enjoys there against the PLA. Also, many analysts have feared that the road would threaten India’s strategic Siliguri Corridor, which is also known as the Chicken’s Neck. It is a narrow strip of land, less than 27 kilometres wide at one point, which provides India the only land access to its seven northeastern states. (However, given the troop density and two key airbases India has in the region along with the mountainous terrain as a natural barrier, the fears of China cutting off the northeast from the rest of India by capturing or targeting the Siliguri Corridor is highly exaggerated.)

Indian troops crossed over to the disputed territory between Bhutan and China and stopped the Chinese from constructing the road. This started the two-and-half month and drew the attention of the world community. Although no firing between the troops of the two sides took place after some initial jostling, India steadily fortified its defences by deploying more troop and military hardware in the area and increased its alert level all along the line of actual control (LAC) with China. (It must be noted that the border between India and China in the Sikkim sector is agreed upon by the two countries and is demarcated.) Indian troops entered an area, which both Bhutan and China claims, “on behalf of Bhutan” by invoking the India-Bhutan treaty of 2007, Article 2 of which says:

In keeping with the abiding ties of close friendship and cooperation between Bhutan and India, the Government of the Kingdom of Bhutan and the Government of the Republic of India shall cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests. Neither Government shall allow the use of its territory for activities harmful to the national security and interest of the other.

Bhutan too issued a demarche to China, with whom it has no diplomatic ties, through its embassy in New Delhi and asked China to stop its road construction in the disputed territory.

Although the area concerned fell under a disputed territory between Bhutan and China, in the 1993 “Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity” between India and China, both countries agreed to maintain the status quo of the trijunction until the territorial disputes are resolved. An all-weather road there would have changed the status quo in China’s favour.

India thus moved its troops citing two things:

- To back Bhutan under Article 2 of the 2007 India-Bhutan Friendship Treaty.

- To stop China from changing the status quo of the trijunction as agreed between India and China in the 1993 Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity (also known as Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement or BPTA) by preventing it from building an all-weather road there.

China’s reaction, India’s resolve, and disengagement

Beijing was taken aback by India’s unprecedented act of moving its troops on behalf of a third country against its soldiers in a territory China claims to be its own. It brought together its military, foreign ministry, official and semi-official mouthpieces to unleash a shrill rhetoric and warmongering against India. Its propaganda ranged from lies and half-truths to the ridiculous, such as the bizarre video released by one of its official mouthpieces – Xinhua News Agency. One of its semi-official mouthpieces, the rabble-rousing tabloid Global Times, also called India’s foreign minister Sushma Swaraj a “liar” and national security adviser Ajit Doval a “schemer”. It was a part of China’s psychological warfare taken from Sun Tzu’s “Art of war” which states: “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

On the other hand, barring just one official MEA statement and Sushma Swaraj’s clarification [YouTube] of India’s stand in Doklam to Parliament, New Delhi maintained a steadfast and dignified silence. Bhutan too avoided discussing the stand-off publicly except when it acknowledged that it had issued a demarche to China asking Beijing to restore the status quo of the territory until the dispute over its sovereignty is resolved.

China had hoped India would back down and withdraw its troops from the site in the face of relentless propaganda and military threat. However, India knew withdrawing would be a strategic blunder that it can never recover from, especially in the Sikkim sector. Also, this would have risked China doing a similar thing in multiple areas along the long and disputed LAC. Apart from this, India had other things at stake as well, such as its credibility among smaller nations in South Asia who China has been trying to woo towards itself in its power game against India.

Beyond South Asia, a unilateral Indian withdrawal from the stand-off would have demoralized countries like Vietnam, who are looking up to India for support in the South China Sea, and jeopardized India’s standing as a reliable partner. With Vietnam, India has defence ties and New Delhi and Hanoi are partners in oil exploration in the disputed sea.

India knew that China can’t defeat India in a military confrontation in the Himalayas because of several factors, some of which are discussed here by military enthusiast and observer Yusuf Unjhawala. In the Sikkim sector especially, the Indian Army holds the tactical advantage of height and terrain over the Chinese. (In 1967, in the same sector, a skirmish between the Indian Army and the PLA resulted in the deaths of around 80 Indian soldiers and 400 Chinese soldiers.)

India had no option but to call China’s bluff and dig itself in Doklam.

Realizing India has effectively stalled its designs in the Doklam area and it can in no way evict Indian forces from there without risking a potentially humiliating military defeat that would have serious geopolitical ramifications for China, Beijing had no option but to stop its road-construction activity in the Dolam plateau and agree to a mutual pullout as demanded by New Delhi. However, it needed a face-saver after painting itself in a corner following all the rhetoric and warmongering it indulged itself in from the day the news of the Doklam stand-off became public. And India gave it one to wriggle out from the pitiable situation. The official statements of the two governments reflect the same:

Indian statement announcing end of stand-off:

1. In recent weeks, India and China have maintained diplomatic communication in respect of the incident at Doklam. During these communications, we were able to express our views and convey our concerns and interests.

2. On this basis, expeditious disengagement of border personnel at the face-off site at Doklam has been agreed to and is on-going.

Chinese statement confirming end of stand-off:

On June 18, the Indian border troops illegally crossed the well-delimited China-India border in the Sikkim Sector into China’s Dong Lang area. China has lodged representations with the Indian side many times through diplomatic channels, made the facts and truth of this situation known to the international community, clarified China’s solemn position and explicit demands, and urged India to immediately pull back its border troops to the India’s side. In the meantime, the Chinese military has taken effective countermeasures to ensure the territorial sovereignty and legitimate rights and interests of the state.

At about 2.30pm of August 28, the Indian side withdrew all its border personnel and equipment that were illegally on the Chinese territory to the Indian side. The Chinese personnel onsite have verified this situation. China will continue fulfilling its sovereign rights to safeguard territorial sovereignty in compliance with the stipulations of the border-related historical treaty.

The Chinese government attaches importance to developing good neighbourly and friendly relations with India. We hope that India could earnestly honour the border-related historical treaty as well as the basic principles of international law and work with China to preserve peace and stability in the border area and promote the sound development of bilateral relations on the basis of mutual respect for each other’s territorial sovereignty.

India didn’t mention about the Chinese side agreeing to its principal demand of halting the construction of the road, which triggered the stand-off and allowed China to save its face. The Chinese too avoided answering the question directly. On being persisted, the Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman, Hua Chunying, said, “Chinese border troops continue to be stationed and patrol (the area) … We will take into consideration all factors, including weather, to make relevant construction plans according to situations on ground.”

What really happened

Information emerging from private sources in South Block have revealed that a close associate of China’s President Xi Jinping called for a meeting with the Indian ambassador to China to negotiate a quick disengagement of the troops in the stand-off. It is not difficult to understand the reason behind China’s sudden change of stance. This was because of two reasons. First, the Chinese realized that the stand-off reached a stalemate and it can’t achieve its objectives there starting with the construction of the road. Also, it was impossible for them to evict the Indian troops by force. With winter approaching, troops of both the sides couldn’t carry on with the stand-off much longer anyway.

Second, the BRICS summit in Xiamen was just a week away. A boycott by Prime Minister Narendra Modi would have been a huge embarrassment to Xi, who tried everything to make this a successful showcase event. Also, after the disastrous Goa summit of the group, the existence of BRICS would have been in jeopardy if India boycotted the summit and China’s failure to ensure the Indian prime minister’s participation in the event would have been blamed for it.

There is another reason that might have acted as a catalyst for China to resolve Doklam at the earliest. The situation in the Korean peninsula was reaching a tipping point with US President Donald Trump warning North Korea’s Kim Jong-un with “fire and fury” over the latter’s missile tests. Xi found himself trapped in a hot oven.

A deal was struck during the meeting between the Indian diplomat and the Chinese official, which was then accepted by New Delhi and Beijing. Following this, an Indian brigadier and his Chinese equivalent held a flag meeting at the stand-off site to negotiate the pullout. The Indian brigadier insisted on a written order from his counterpart’s superior authority. India also insisted that all troops and construction material will have to be withdrawn to the pre-June 16 position. The Chinese produced the document and agreed to the Indian demands.

However, the Chinese wanted a face-saver and asked for an Indian withdrawal first.

India agreed to a gap of just a few hours. By the end of the day, troops of both the countries were back to their old posts. In this way, the Chinese demand, that Beijing so strongly, publicly, and repeatedly made, that India withdrew first was technically met.

(It must be noted that Chinese border guards always patrolled the Dolam plateau under the watch of Indian and Bhutanese troops from the heights nearby. The “area” mentioned was deliberately kept vague. It could mean any part of the Doklam plateau, not necessarily the disputed territory. Also, as part of the understanding between the two countries, India won’t contest the Chinese remarks on its “(road) construction plans, factors and weather permitting”.)

***

Although India gave Xi, a face-saver this time just before the BRICS summit and the 19th congress of the Chinese Communist Party this autumn, in which he seeks a five-year extension of his term in office, India must not be complacent in its preparedness against China as the threat of future hostilities remain just as before in the absence of a settlement of the border dispute. China has been gradually salami-slicing Indian territory a few hundred metres a time in the Himalayas. It is estimated that India lost over 2,000 sq km of territory to the Chinese in the last 10 years alone. Without the boundary dispute between the two countries yet to be settled, China will not cease to stop its land-grabbing activities without firing a bullet.

Also, a Doklam-like stand-off is likely to happen in areas on the LAC where the Chinese have an advantage over the Indians, like in Jammu & Kashmir’s eastern Ladakh, Uttarakhand’s Barahoti sector, or the “Fish Tail” area in eastern Arunachal Pradesh’s Chaglagam sector, etc. Besides, Doklam was a personal setback for Xi as a leader, which he is unlikely to forget.

Need for an all-round roadmap

Military

The best thing that emerged from the Doklam stand-off for India is that it kicked India out of the slumber and pushed it fast-track its defence preparedness and speed up building its infrastructure along the LAC. The end of the stand-off must not make India lower its guard. It must show the same urgency in these two areas as it showed in the last two months and extend it to all along the LAC, which is over 4,000km long.

India must also take this as a catalyst for military reforms. It desperately needs a joint command of the three services – Army, Air Force, and Navy. (China already has joint commands at theatre levels.) Successive governments have dragged their feet in implementing this critical reform. If the government is still undecided, it must at least implement joint services commands at three key theatres – Eastern, Northern, and Western to counter a two-pronged threat from China and its client state Pakistan.

Electronic and cyberwarfare

The Doklam incident also makes India to do a reality check and upgrade itself in electronic measures to safeguard itself from an almost inevitable Chinese cyberattack in the event of a future conflict. As India and China are both nuclear-armed countries, they are highly unlikely to enter a full-fledged conventional war against each other that may result in a major loss of life, territory, or infrastructure. However, the possibility of sector-specific high-intensity skirmishes remains high. In such a situation, China will try to minimize its losses by neutralizing Indian tactical advantages wherever they are – in land, air, and sea. China has made rapid advancements in its cyber- and electronic-warfare capabilities in recent years. Hackers from PLA’s Unit 61398 were believed behind some high-profile hacking in the US. There are speculations that the Chinese were behind the crash of IAF’s Sukhoi-30MKI in Arunachal Pradesh earlier this year and the recent collisions of the US navy warships.

Besides expertise in cyberwarfare, China has been developing technologies for its smart weapons and ammunitions since it witnessed the US campaign against Iraq in Gulf War I, in 1991. Former commander of Indian Army’s Northern Command Lt Gen HS Panag has discussed these “smart” capabilities of the Chinese military and the realistic threat they present to India in his article “How will Chinese use of force in Doklam manifest?”

Needless to say, India has no option but to gear up for this challenge by expeditiously setting up a unified cybercommand and develop technologies for not just countering Chinese smart weapons, but hit the Chinese back with smart weapons of its own.

Apart from this, India must take its domestic cybersecurity very seriously. Already, Chinese companies dominate the smartphone market in India and are involved in a major way in building and setting up our communications and power network across the country. This poses a grave cybersecurity threat. There is no guarantee that our communications and power networks are not compromised and Chinese hackers won’t sabotage them in the event of hostilities between the two countries. Although the government has taken some measures to counter this threat in the communications sector, it is probably not enough. Also, it has not done anything yet to counter the possible threats Chinese companies may pose to our power sector. One can easily visualize what will happen in the event of a large-scale breakdown in communications and power distribution even in peacetime, let alone during a war.

The Indian government will have to quickly address these issues and hammer in measures at the earliest to prevent such a scenario.

Geostrategic

The result of the Doklam stand-off has given India a geostrategic boost to India in Asia. Not only it has hiked India’s credibility among the South Asian nations who are sitting on the fence between India and China, like Nepal and Sri Lanka, it has also given confidence to other nations, like Vietnam, to bank upon India’s support in its economic activities against China’s open threat in the disputed South China Sea.

Vietnam is the pivotal Southeast Asian nation in Modi’s “Act East policy”. New Delhi already has an oil-exploration pact with Hanoi along with defence ties. It must now work upon a framework with other nations with claims to the disputed sea to jointly explore for oil and harvest resources from the sea without giving in to China’s threats, like Vietnam gave in recently. India must launch a diplomatic campaign in which it must give an understanding to these nations that India will stand by them against a Chinese security threat without necessarily entering a direct military pact with them. This would also work out to India’s advantage in the Indian Ocean region to counter Chinese designs in its own backyard.

China’s arch enemy is Japan – a country that has very close and friendly ties with India. Japan also has one of the largest navies in Asia and probably the best equipped as well. Japan is also a permanent partner in the Malabar biennial naval exercises involving India and the United States. India must not shy away from conducting joint naval patrolling with Japan in the Indian Ocean region, Malacca Straits, South China Sea, and even in East China Sea (where Japan and China has a dispute over the Senkaku Islands), if Japan wants it. The US is unlikely to discourage India’s naval forays with Japan in these waters.

This is also a great opportunity for India to implement its own maritime silk-route project – Mausam – that Modi envisaged a couple of years ago. The Mausam project promises not just to boost India’s economy along with the South and South Asian countries, but it also compels India to further develop its maritime military strength to safeguard its economic and security interests in the blue seas.

Neighbourhood watch and diplomacy

Bhutan has stood by India throughout the latter’s stand-off against China and once again proved to be its closest friend. New Delhi now must speed up the various infrastructure-building and hydroelectric projects it has undertaken in the Himalayan kingdom. At the same time, it must continue to provide subsidized fuel to the country. A few years ago, ties between the two countries were strained when India cut fuel subsidies to Bhutan.

Similarly, India must reach out to fence-sitters between India and China in its neighbourhood. New Delhi must avoid situations like it found itself in the violent aftermath of Nepal’s promulgation of its new constitution, which led to the unofficial blockade of India-Nepal trade routes. This led to widespread resentment against India among the Nepalese people and made Kathmandu lean towards Beijing for help. New Delhi squandered the immense goodwill India gained in Nepal for its rescue and relief work and the aid it extended to Kathmandu following the devastating 2015 earthquake there. It happened because of New Delhi’s shortsighted cross-border politicking in a particularly sensitive time. Due to the two countries’ historical, cultural, geographical, and demographical closeness, both the nations have very high stakes in maintaining friendly ties with each other.

Although India has a friendly government in Sri Lanka under the leadership of President Maithripala Sirisena and there is no major dispute with the island nation, China’s hold on the country remains a concern for New Delhi. Sri Lanka is a major “pearl” in the so-called “String of Pearls” that China hopes to encircle India with. India must resolve all outstanding issues with Sri Lanka including building a framework for resolving the disputes involving the fishermen of both the countries. It must also up its economic activities in the country and help Colombo increase its trade and develop its infrastructure. The recent Hambantota port deal between Colombo and Beijing should come as a relief for New Delhi, but just so. China still retains the control of the port for 99 years. India should keep a sharp eye on it with Sri Lanka’s assistance and some clever diplomacy would ensure that.

Maldives has been a thorny concern for India in the past few years with a pro-China and somewhat hostile government of Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom coming to power. The Maldivian opposition is friendly towards India. However, after Modi’s initial cold-shouldering to Gayoom, he changed his policy towards him despite the Maldivian president has been on a campaign to crush all democratic institutions in his country. This helped the ties between New Delhi and Male to thaw. So far, India has been able to keep things in check in the country when it came to Male’s relationship with New Delhi. India must not withdraw its eyes from the island nation and constantly strive to see ties don’t deteriorate from here.

Information war

During the Doklam stand-off, China revealed how to fight the information war and India must take major lessons from it. Although India’s silence throughout the stand-off was generally appreciated, it also allowed the Chinese to get away with lies and half-truths, especially when it released a 15-page document [pdf] on the stand-off with the elaborate title “The Facts and China’s Position Concerningn Border Troops’ Crossing of the China-India Boundary in Sikkim Sector into the Chinese Territory”. In the document, Beijing conveniently omitted facts that goes against its stand. New Delhi failed to counter it with its own set of facts and let Beijing seize the control of the narrative. This fits well with its doctrine, as cited in a 2009 Pentagon report to the US Congress, which says: “It is not the best weapons that wins today’s wars, but rather the best narrative (even if it is a false narrative).” Indian geostrategy expert Prof Brahma Chellaney has discussed how China wages psychological warfare in his article here. Some individual Indian commentators and experts took it upon themselves to counter the Chinese “fact sheet” on Doklam on social media, but they didn’t catch much attention in India, let alone in foreign countries.

The Doklam stand-off also exposed the behaviour of the Indian media, which unlike the Chinese media is independent. Throughout the stand-off, many Indian news agencies and media outlets – print, digital, and television – dished vile and bellicose Chinese propaganda filled with lies, half-truths, and rhetoric as “news” to not only its domestic consumers, but also to international observers keen to learn about the developments on Doklam from the Indian media. India’s information and broadcasting ministry failed to issue any advisory or guidelines to these media organizations to keep national interests in mind. It was shocking to say the least.

India needs to understand the importance of information war in today’s geopolitics. It can’t afford its adversaries run away with the narrative to confuse foreign governments and preempt them from siding with India. The sooner New Delhi wakes up to this new-age information warfare, the better position it will be in if such a scenario presents again. And it will.

Leveraging trade as geopolitical weapon

Another important thing India can learn from China is weaponization of trade. Beijing never shied away from using trade to punish countries that went against its wishes and interests. In 2016, China cracked down on trade with Mongolia when Ulaanbaatar allowed the Dalai Lama to visit the country. Beijing considers the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader as a political threat and a secessionist. Recently, China imposed sanctions on South Korean companies because Seoul went ahead to allow the US to deploy its THAAD anti-missile system against the North Korean ballistic-missile threat. Beijing believes the deployment is designed not just to thwart North Korean missiles, but also China’s strategic missiles.

During the Doklam stand-off, trade between India and China went on without hindrance. China, which stopped the Indian Kailash-Mansarovar pilgrims from taking the Nathula route to the holy peak in the wake of the stand-off, didn’t stop trading through the route with India. China enjoys a trade surplus of over $61 billion with India in the $72 billion overall trade between the two countries. In this way, India contributes to China’s economic, political, and military hegemony in Asia. India failed to leverage its trade deficit during the Doklam stand-off to hurt China where it hurts most – its slowing economy.

In the future, India shouldn’t shy away from imposing steeper tariff on Chinese imports or even impose sanctions on companies doing business in India that have ties with the PLA and other anti-India organizations, including the bellicose state-owned Chinese media.

***

As discussed earlier, the Doklam disengagement doesn’t mean that China wouldn’t present such a situation to India again. Many years ago a retired senior Indian military official said the Chinese seldom have a Plan B. Their Plan A is usually so good that they didn’t really needed a Plan B. However, if it came to that, China would take a back step and come back when they have sorted the failings of their Plan A. That China would try to grab land by making incursions in the long unresolved border is a given. Also, this time they would also take into account the kind of military response they faced from India. They would be well prepared for a short but sharp local war in which they would seek to defeat India.

However, if India stays alert without letting its guard down and keeps up the pace of military, infrastructure, geostrategic, and diplomatic preparations, Beijing would be compelled to sit with New Delhi for permanently resolving the border dispute and give up its land-grabbing policy in the Himalayas.

Postscript

At around 8am on June 18 this year, while on my way to Nathula (Nathu La) from Gangtok, my car had to stop just as it began the climb about a kilometre from the checkpost where the passes and identities of travellers travelling to the India-Tibet border are checked. A bulldozer on its way up had broken down in the middle of the narrow road blocking the traffic. The local police made all the upward-bound vehicles stop and line up one after the other on the left side of the road. Due to restrictions, there was no vehicle coming down the mountains at that time. I also saw a column of Army trucks also stuck in the blocked road ahead of us.

On asking a police officer, I was told that the convoy, along with the bulldozer, was going to an area near the border where Chinese soldiers “entered Indian territory” in the “Chumbi (Valley) side” and were “constructing things”. The Army bulldozer was apparently being sent to “smash those things”. The policeman also cautioned me “not to make the news viral”. I asked a soldier standing near the stalled convoy and he told me a similar thing after some hesitation. I thought it wasn’t a big deal as such Chinese activities along the LAC was common.

Was cautioned by the 56″ system not to make this “viral”. I’m a small tweeter. China made a many-mile incursion 6km right of #Nathula here. pic.twitter.com/wax67u8J11

— Jayanta Bhattacharya (@goldenarcher) June 18, 2017

Later in the day, on my way back from Nathula, I took a couple of photos of the direction where the “action” was taking place and tweeted one from Gangtok as my mobile carrier had no network all along the route. Little did I know then this was the beginning of the second-longest military stand-off between India and China in history after the famous 1987 Sumdorong Chu stand-off in Arunachal Pradesh, which lasted for over a year.

And unwittingly, I was the first to break this news to the outside world with my tweet.